Mapping the Holy Land II

Cartographic Treasures from the Trevor and Susan Chinn Collection

-

October 8 2013 - March 2 2014

Curator: Ariel Tishby

-

ancient maps

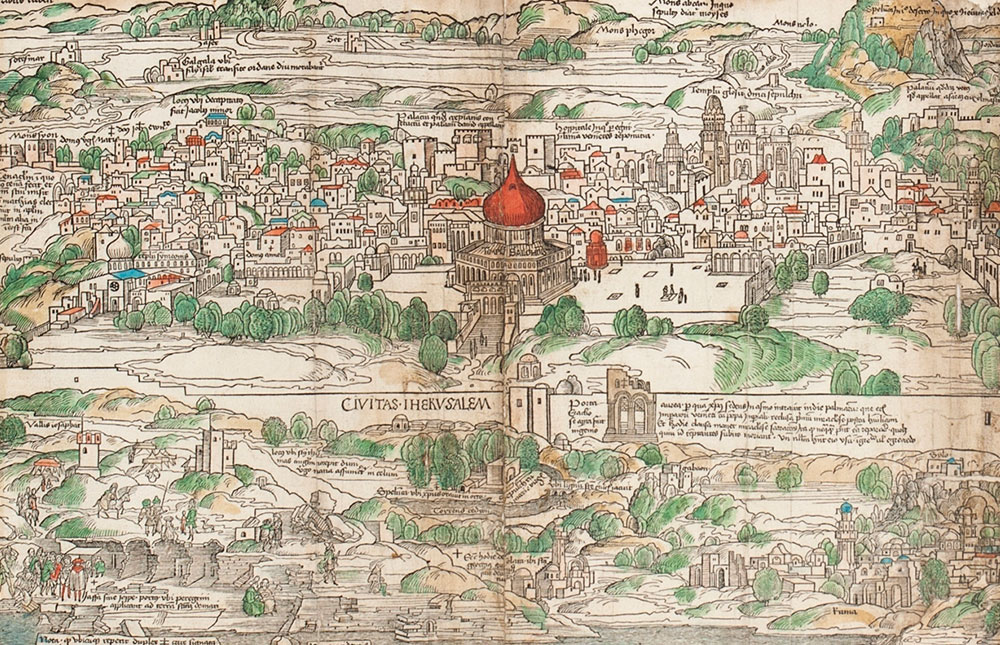

The centerpiece of this display is Bernhard von Breydenbach’s seminal 1486 map of the Holy Land. One of the first printed maps, it was created from three woodblocks by the Dutch artist Erhard Reuwich. Breydenbach, a priest and nobleman from Mainz, embarked on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in April 1483, returning to Germany in January 1484. He was accompanied by a large entourage, including Reuwich, who was asked to draw the sights. The pilgrims visited Jerusalem and its vicinity, focusing on Christian holy sites, with a smaller delegation continuing to the Saint Catherine Monastery in Sinai. Upon returning to Mainz, the travelers began to compile a manuscript documenting their journey. Published in Latin in 1486 and soon translated into several languages, it was the first printed illustrated work to feature an accurate map of the Holy Land and quickly became a bestseller, largely owing to the included woodcuts. The Breydenbach map shows the area from Damascus and Beirut in the North to Alexandria and Mecca in the South. At the center, rotated 180 degrees, Jerusalem is depicted on a large scale and in unprecedented detail. Oriented to the east, the map thus provides a bird’s-eye view of Mamluk Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives looking west. Christian holy sites are emphasized and accompanied by a caption, while small crosses indicate those places in which one could be granted an indulgence - a temporary release from the punishment of sin. Merging the journey to earthly Jerusalem with the journey to heavenly Jerusalem, the map conveys the true purpose of a pilgrimage: walking in Jesus’ physical and spiritual footsteps as a means of purifying the soul. The manuscript and its illustrations offered European Christians the means of experiencing a voyage too expensive, difficult, and dangerous for most to undertake. The six other maps on view here provide evidence that many cartographers who had never visited the Holy Land relied on original “prototypes,” often combining elements from more than one map. Du Perac and van Schoel misunderstood the inverted orientation of Jerusalem in the Breydenbach map, presenting their own maps as oriented eastward and copying Breydenbach’s positioning of the Mount of Olives to the south (left) of Jerusalem. Several cartographers also ignored the rebuilding of the walls of Jerusalem in 1537-42, copying instead the breached walls and partially destroyed Golden Gate until the 18th century. In this special display, visitors are invited to spot the differences between the 1486 prototypical map and those it influenced over the course of two hundred years.

- Mar 01Mar 08Mar 15Mar 22Mar 29Apr 05Apr 19Apr 26

- Mar 21Mar 22Mar 28Mar 29Apr 05Apr 19Apr 26

- Mar 17Mar 20Mar 24Mar 27Mar 31Apr 03Apr 07Apr 10Apr 21Apr 24Apr 28

- Mar 17Mar 24Apr 07Apr 21Mar 31Apr 28

- Mar 17Mar 20Mar 24Mar 27Mar 31Apr 03Apr 07Apr 10Apr 15Apr 16Apr 21Apr 24Apr 28

- Mar 24Mar 31Apr 07Apr 21Apr 28

- Mar 25Apr 01Apr 08Apr 22Apr 29

- Mar 18Mar 25Apr 01Apr 08Apr 22

- Mar 25Apr 01Apr 08Apr 22Apr 29

- Apr 22

- Apr 22

- Apr 22May 20Jun 19Jun 24

- Mar 06Mar 13Mar 20Mar 27Apr 03Apr 10Apr 17Apr 24

- Mar 06Mar 13Mar 20Mar 27Apr 03Apr 10Apr 17Apr 24

- Mar 06Mar 13Mar 20Mar 27Apr 03Apr 10Apr 17Apr 24

- Apr 24May 27

- Mar 20Mar 27Apr 03Apr 10Apr 14Apr 17Apr 24

- Mar 25Apr 24