Uri Gershuni, Apollo and the Chimney-Sweeper

6 Artists 6 Projects

-

February 11 2015 - August 22 2015

Curator: Noam Gal

-

Photography

- : Uri Gershuni

In the early 1840s, soon after he invented a way to reproduce images that would change history as a new medium - photography - the English scholar and scientist William Henry Fox Talbot contemplated one of his first photographs. The image was a simple cityscape he had captured while in Paris. Talbot wrote of it: "A whole forest of chimneys borders the horizon: for, the instrument the camera chronicles whatever it sees, and certainly would delineate a chimney-pot a chimney-sweeper with the same impartiality as it would the Apollo of Belvedere." In Western culture, this ancient Roman sculpture of Apollo - god of the sun, of prophecy, and of art - symbolized all that was beautiful and perfect. The sooty chimney sweep, on the other hand, was an emblem of the impoverished urban working class that the Industrial Revolution had created.

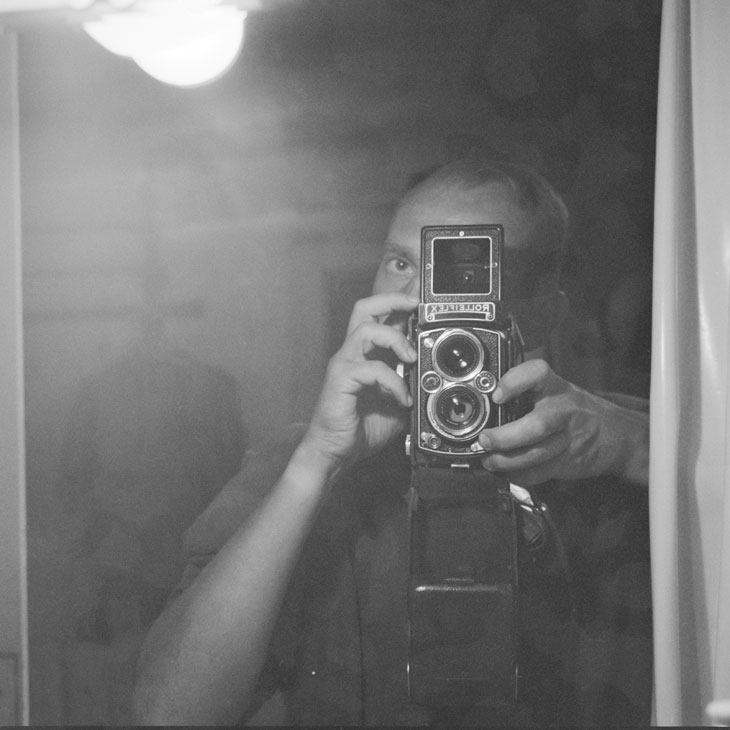

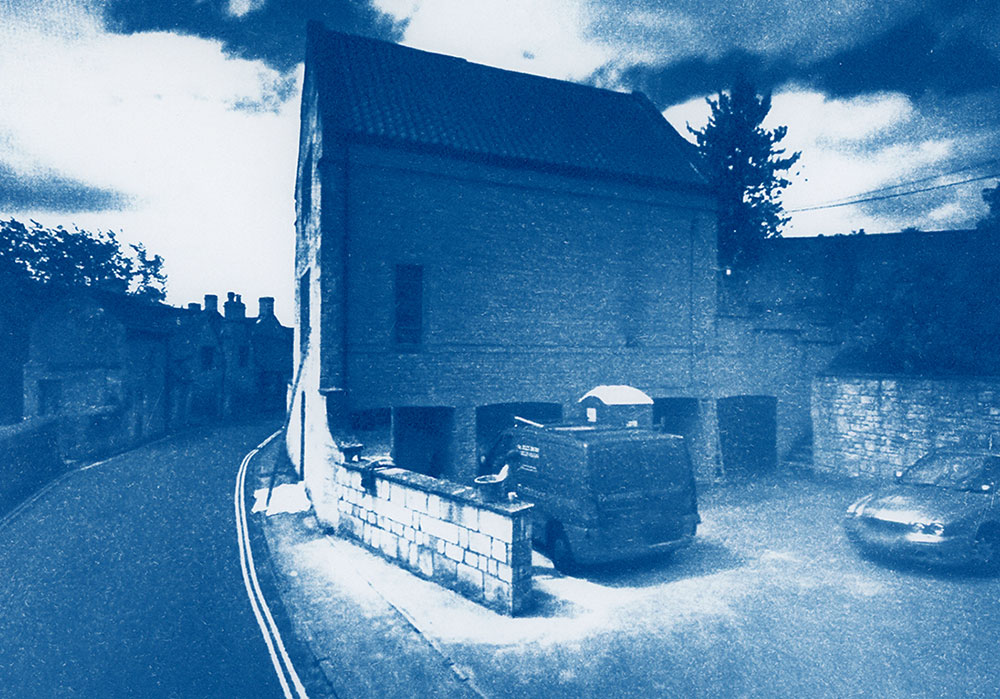

This equation of sun and soot, sublime art and grueling labor, has been reconsidered by the artist Uri Gershuni, who was born in Israel in 1970. Gershuni traveled to Lacock, Talbot's ancestral village in England, but not as a tourist taking in a scenic site. First, he wandered around Lacock with a pin-hole camera that produced a series of murky, mysterious photographs entitled "Yesterday's Sun." His second visit was virtual, through Google Street View alone, but he transformed the screenshots he chose into cyanotypes, blue-tinted photographs that result from an elaborate 19th century technique. Finally, instead of regarding the outside world in any way, Gershuni turned inward to his own body, imprinting photographic paper with his sperm or fingerprints.

Following Talbot and his ideas about the indifference of the camera, which impartially equates the lowly and the lofty, darkness and enlightenment, led Gershuni to camera-less photography. As his work progresses, the sun - which Talbot called "the pencil of Nature" - loses its power. Is this perhaps an indication of the effect the industrial age (which witnessed the invention of the camera) has had on the earth and its sunlight?

Untitled, from "The Blue Hour", 2014, Collection of the artist

- Apr 21Apr 24Apr 28May 05May 08May 12May 15May 19May 22May 26May 29

- Apr 21Apr 28May 05May 12May 19May 26

- Apr 21Apr 24Apr 28May 05May 08May 12May 15May 19May 22May 26May 29

- Mar 24Mar 31Apr 07Apr 21Apr 28

- Mar 25Apr 01Apr 08Apr 22Apr 29

- Mar 25Apr 01Apr 08Apr 22Apr 29

- May 01

- May 01

- Apr 26May 02May 03May 09May 10May 16May 17May 23May 24May 30May 31

- Apr 22May 06

- May 06May 27

- May 06

- May 06

- May 06Jun 10

- May 08

- Apr 24May 08May 15May 22May 29