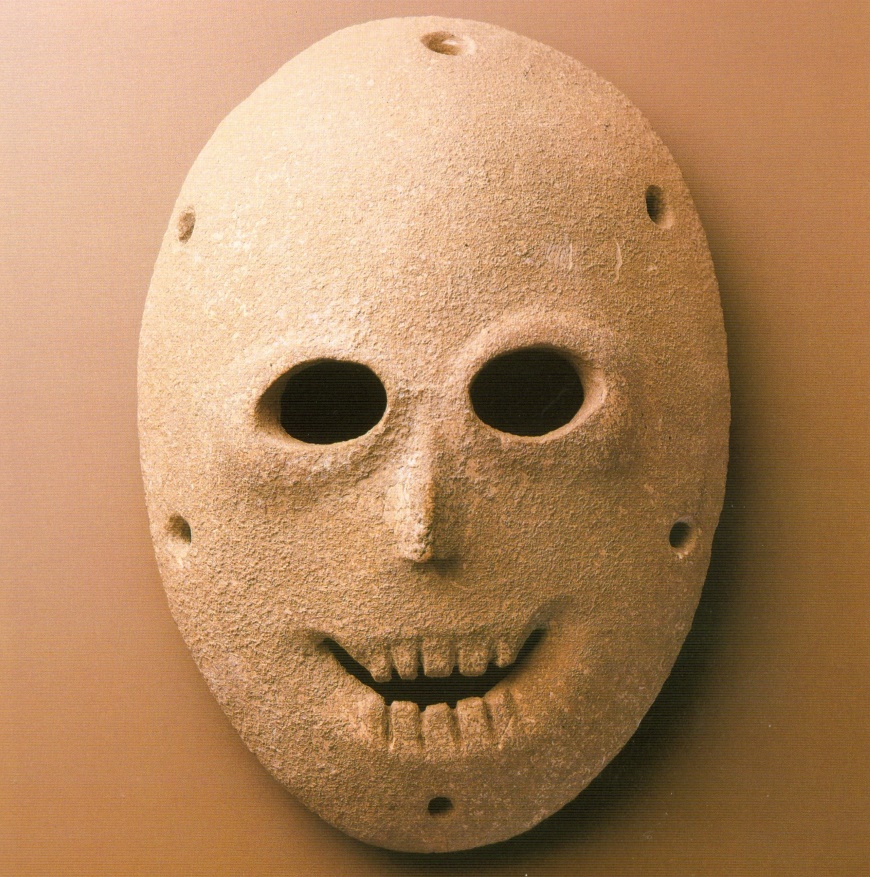

Nicolas Poussin, The Destruction and Sack of the Temple of Jerusalem

A Rediscovered Masterpiece

-

June 1 1999 - January 30 2001

Curator(s): Shlomit Steinberg

-

Oil on canvas

- : Nicolas Poussin

Nicolas Poussin was the foremost exponent and practitioner of seventeenth-century Classicism. This work from his early Italian period (1625-1626) was commissioned by Poussin' patron Cardinal Francesco Barberini, nephew and secretary of Pope Urban VIII, and was offered as a gift to Cardinal Richelieu, the French head of state. Barberini led a papal legation in a vain attempt to reconcile France and Spain, at the time engaged in a bloody war. Poussin draws a parallel in the painting between his patron, the would-be peacemaker, and the enlightened pagan emperor Titus, who tried unsuccessfully to prevent the ruin of Jerusalem and its temple. The composition is divided between the image of the Temple engulfed in flames in the background and the chaotic struggle, dominated by the striking figure of Titus on his white mount, in the foreground. A sense of drama, with the clash of arms and flashes of golden light from the Temple vessels, suffuses the entire work. Classical Roman architecture and sculpture provided sources for Poussin's painting. The scene seems to be a Roman city: the soldiers' dress is taken from reliefs on Roman sarcophagi; the facade of the Temple resembles that of the Pantheon; the figure of Titus was inspired by the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius in the Capitoline; and the menorah derives from the famous depiction on the Arch of Titus. After Richelieu's death, the painting was inherited by his niece, who then sold it. It changed hands many times and eventually reached England. Its whereabouts were unknown from the late 1700s until 1995, when it was rediscovered by the art historian Sir Denis Mahon, restored to its original state, and donated to the Israel Museum in 1998.

MORE EXHIBITIONS

More Events

- Apr 21Apr 24Apr 28May 05May 08May 12May 15May 19May 22May 26May 29

- Apr 21Apr 28May 05May 12May 19May 26

- Apr 21Apr 24Apr 28May 05May 08May 12May 15May 19May 22May 26May 29

- Mar 24Mar 31Apr 07Apr 21Apr 28

- Mar 25Apr 01Apr 08Apr 22Apr 29

- Mar 25Apr 01Apr 08Apr 22Apr 29

- May 01

- May 01

- Apr 26May 02May 03May 09May 10May 16May 17May 23May 24May 30May 31

- Apr 22May 06

- May 06May 27

- May 06

- May 06

- May 06Jun 10

- May 08

- Apr 24May 08May 15May 22May 29